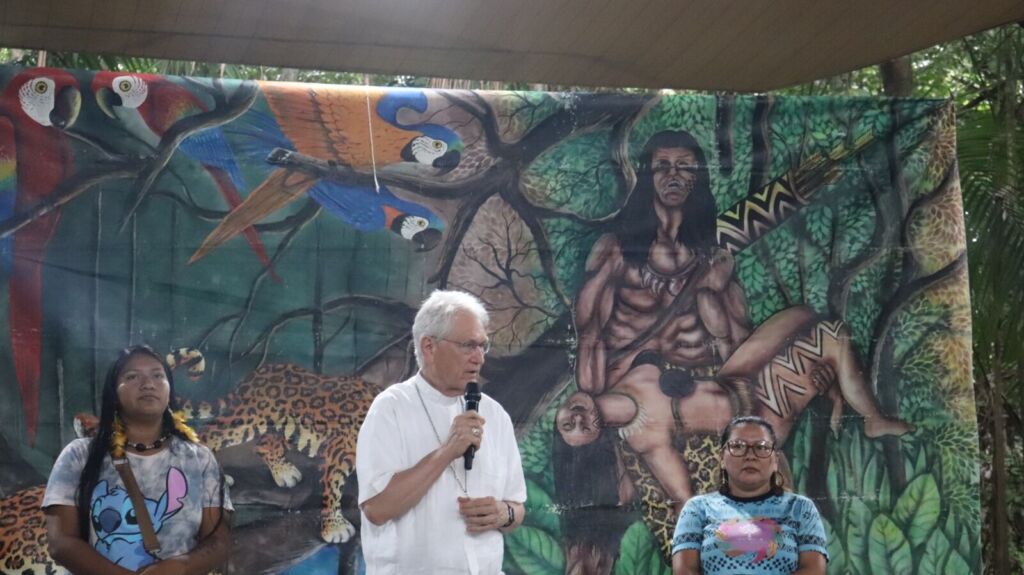

On October 5, the Archdiocese of Manaus celebrated the Jubilee of the Original Peoples. The participants, belonging to different peoples, went on pilgrimage from their own communities on the outskirts of the city to Parque do Mindu, the place chosen to celebrate this moment of faith and culture that brought them together around our Cardinal Archbishop Leonardo Steiner.

“The answer is us”. This was the phrase chosen by the Original Peoples for their Jubilee held in Mindú Park in Manaus. Those who know the Amazonian capital are aware of the immense urban challenge the city faces. The processes of occupying the territory have led to a distancing of the inhabitants’ relationship with nature.

On the day that the Archdiocese of Manaus was celebrating the Jubilee of Original Peoples, heavy rain hit the capital of Amazonas. It’s poetic to think that during the speech by Cardinal Leonardo Steiner, Archbishop of Manaus, on the need to create a new relationship with nature, the rain started. However, it’s likely that this event is linked to climate change and that’s why we’ll think about this day from the perspective of what was experienced in Mindú Park.

Mindú Park is one of the few forested areas in the middle of the city with a wide distribution of fauna and flora. It is a great example of disharmony and recovery, with areas of regeneration previously degraded by deforestation. It is crossed by one of the city’s largest streams, which is polluted along its entire length, but also has the possibility of still-preserved springs. The area is one of the last refuges for an endangered small monkey, the collared marmoset (Saguinus bicolor).

This is a short excerpt. In it, we remember the breaking of the link between God and his creatures in the book of Genesis (9:12-17). For this reason, experiencing a jubilee in this park is profoundly prophetic and compromising. It is an invitation to realize our relationship with the whole of creation since, in the words of the cardinal, “it seems that society is deaf. It seems that hearts are closed and don’t realize how important all creatures are for us to be able to live, to live together”.

The venue was an open-air auditorium. There was a roof that protected us from the heavy rain, but it showed its precariousness with numerous leaks. On the open sides, we found ourselves embraced by the forest. And when the rain came, accompanied by a strong gale, we were moved to occupy just one side of the auditorium. There was no panic or fear. We were connected, we felt part of it.

Meanwhile, another dynamic was taking place in the avenues of the historic city center of Manaus, which were paved over the beds of the igarapés and were being heavily flooded due to the heavy rain. In the videos that circulated on social media, it was possible to see the water occupying the space where the streams used to be. This reveals a structural problem, but also an erasure, an aversion to our deepest roots: the city of water has grown, suppressed and polluted its waterways.

This brief presentation is so that, when we think about responses to climate change, we break with society’s mentality of domination. In this way, we remember the archbishop’s invitation: “May God help us and may you (indigenous peoples) help us to be ever more a reason for hope, a reason for transformation and not for destruction”. It’s a paradigmatic call for ecological conversion, guided by hope that doesn’t disappoint.

In such a complex context, to say that the answer lies with the original peoples is to assume a way of seeing the world that escapes the stagnant dynamics that have been perpetuated throughout the construction of societies. It means returning to a harmonious, attentive and careful way of living.

Harmonious because it respects the time and space of creatures. Attentive because it perceives and accepts the differences of each individual. And careful, because it recognizes fragility, need and appreciates without wanting to dominate for its own sake, without destroying dignity and life in all its manifestations.

Although the Amazon has gained prominence on the world stage, many of the narratives do not include the peoples who inhabit the territory. This way of looking at the Amazon from above, just as a big green carpet, has excluded, neglected and marginalized its population. This is revealed when we hear the cries and appeals of the indigenous, quilombola and riverine brothers and sisters who attended the Jubilee.

Thinking up a new narrative about the Amazon requires us to abandon the assumptions instilled throughout the educational and human process. This requirement means giving up our securities so that there can be a new form of relationship with nature. And the native brothers demonstrate exactly how this can happen, in a non-linear but circular process of passing on learning.

It is therefore essential that the processes of listening to the peoples are constantly resumed. Let their ancestral teachings be taken into account in all our attempts to re-establish relations with nature. We cannot allow ourselves to be dominated by utilitarian logic, nor can we think of a socio-environmental organization that disregards those who have historically transformed the way we live with the forest and its resources.

Emmanuel Grieco N. Barroso,

A young man from Manaus who works for the Archdiocese of Manaus.

Journalism student, Federal University of Amazonas (Ufam)